Among the extraordinary array of figures who have appeared in kitchens over the years to feed their clients, win the hearts of their students and inspire their colleagues, one of the most memorable was a brilliant, eccentric, magnetic woman named Josephine Araldo (1897–1989).

As is sometimes the case with highly talented people, she was known to those to whom she was known—and perhaps not to many others. We cannot even find a proper obituary for this energetic little powerhouse, yet she rubbed elbows with the famous, befriended and even mentored those who went on to greater things, and commanded respect and affection from her own special following.

Born in rural Brittany, she gardened from childhood and learned to use what she grew to make food that “tasted like itself.” Deciding on her vocation while still in her teens, she went to Paris where she studied at the Cordon Bleu with, among others, the great Henri-Paul Pellaprat.

She worked briefly for luminaries in the French government, but in 1924 she was asked by an American dinner guest to come work for his family in San Francisco. That she did, and although she remained in California, she made many return trips to France to visit and to seek additional training. In time, she was fully engaged in teaching both amateurs and professionals, and her West Coast reputation and devoted following grew.

Although formally trained, her kitchen work was far from orthodox. Brilliantly instinctive, she knew when to follow the rules and when to take off and fly. Many fine cooks, ranging from Alice Waters to Marion Cunningham, came to see her and to absorb what they could from both her technique and her keen sense of what worked.

Meantime, her roster of clients grew, some of them famous—dancer Isadora Duncan, the great soprano Lily Pons and her husband, conductor Andre Kostelanetz—and many more who loved her food and her effusive manner.

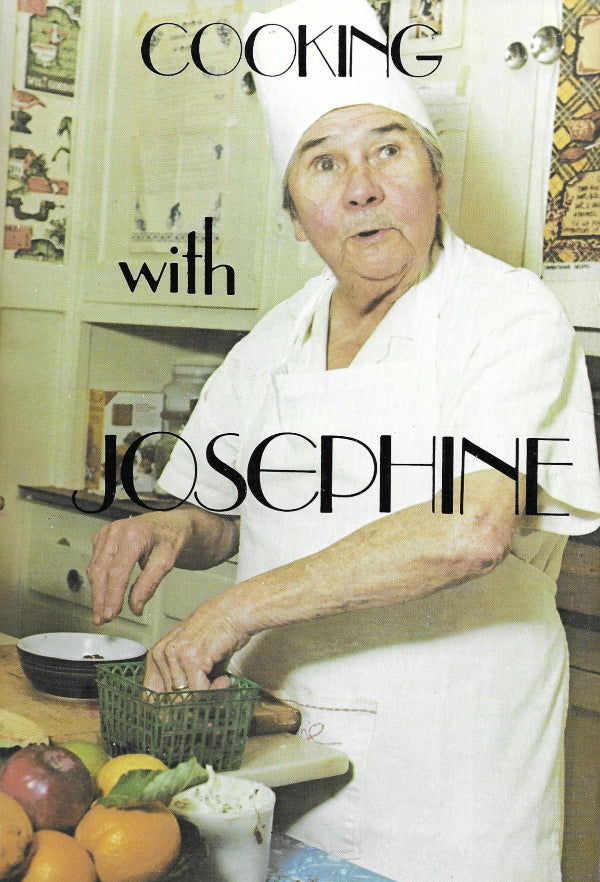

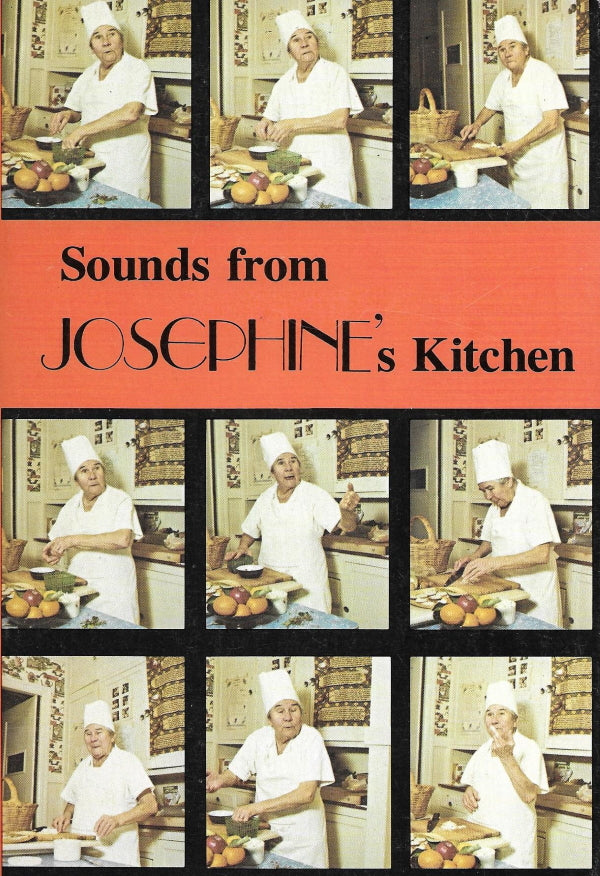

We offer here her two earliest books. Cooking with Josephine (1977) and Sounds from Josephine’s Kitchen (1978) tell much of what this amazing cook was all about. Presenting what appears to be traditional French home food (although one book does have a seven-page chapter entitled “Haute Cuisine”), they are threaded through with anecdotes, biographical detail and lots of informal advice.

Sounds from Josephine’s Kitchen delivers what it promises: Josephine sings when she cooks (“You cook better,” she claims), and at the back of the book there is laid in a small 33-⅓ RPM record of the chef at work, sharing her musical inspiration and bits of kitchen wisdom. Even Julia Child never tried that.

Both books were issued only as quality paperbacks, and—uncommon with these titles—are unused and in Fine condition. Both contain appealing scrap-book style black-and-white photographs. The earlier book is a second printing, the later is a first edition.